If it’s your challenge and you’re happy with it, that’s the most important thing.

-Ueli Steck, Alpinist

April 2, 2021

I didn’t look down at the 1,000-meter steep north face below me. My climbing partner, Patrick, removed the last ice screw from Glacier du Géant on Aiguille du Midi. Connected with 50 meters of rope and no ice screws between us, crampons and ice axes were our only anchor to the mountain.

One ice screw dangled from my harness, but the unconsolidated and porous snow on top of the glacier meant it would be worthless protection against a fall.

“Slow and steady,” I yelled. If Patrick responded, I didn’t hear him. We moved diagonally from right to left on the 55-degree glacial face each focused on finishing the climb.

After 11 hours and 2,700 meters (~9,000 feet) of climbing, the moment was too intense to feel tired. My hands kung-fu gripped my ice axes. Globs of ice accumulated on my pants when I pressed my knees against the snow for a rest. Skis on my pack tugged my shoulders backward as they swayed side-to-side. Kicking my crampons deep, 4-5 times with every step, I forgot about my numb, frostbite-prone toes. We were the only climbers on the mountain and there was no evidence that anyone had climbed this route recently.

I finally exhaled at the scratchy, squeaky noise of a hollow ice screw placed in solid blue ice. Ten meters below a snowy lip, a short vertical climb was more formidable than I expected. For the second time that day, I down-climbed and waited for Patrick to arrive with his collection of ice screws.

Exiting the Mont Blanc Tunnel in Chamonix, France in February 2021, felt like seeing an ex-girlfriend for the first time after a breakup. I was still in love, but I knew we were better off apart. The climbing mecca was my home during a two-year sabbatical from 2018 to 2020 and this was my first trip back since.

When France mandated all ski lifts and resorts closed in the winter of 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, this was a rare opportunity for Chamonix’s fervent alpinists and ski mountaineers to have its world-class climbs and ski descents, including Aiguille du Midi, all to themselves. Conditions were favorable, and the extra 1,000 to 2,000 meters of vertical approach without the assistance of lifts didn’t deter Chamonix’s mountain people.

Mega routes like the north faces of Les Drus and the Grandes Jorasses were seeing plenty of action. I wasn’t ready to take them on—but I didn’t want to miss out on the fun.

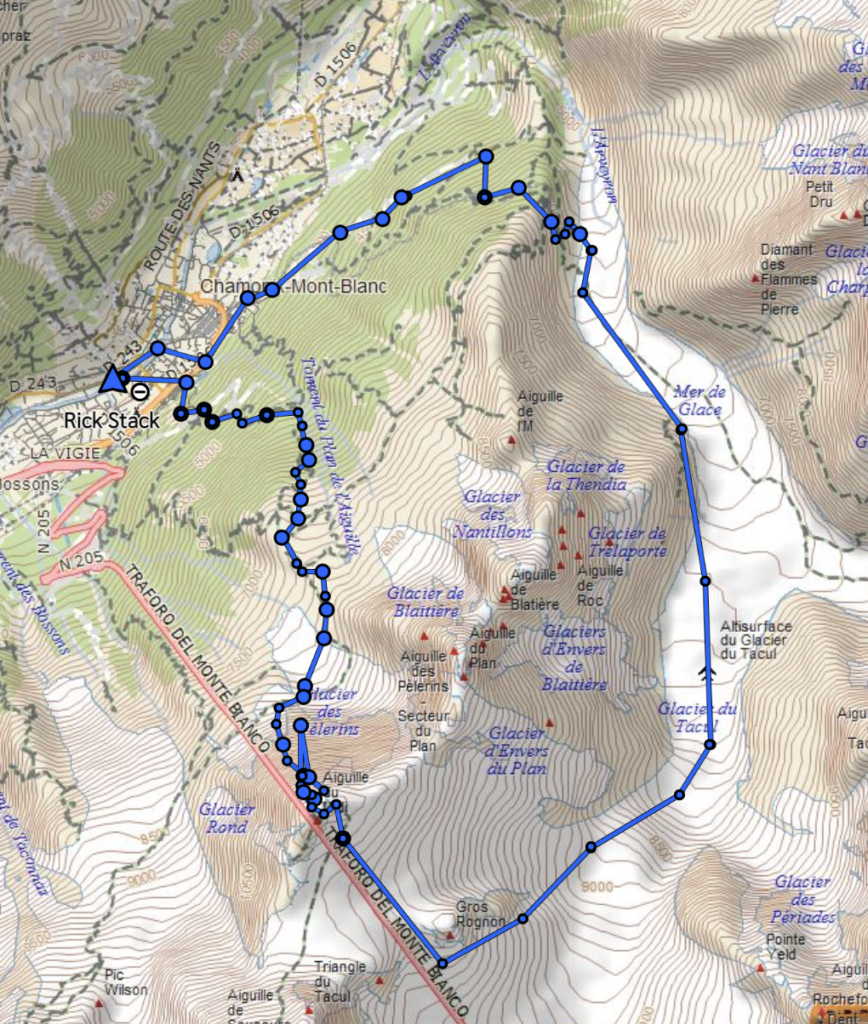

Climbing the north face of Aiguille du Midi from Chamonix in alpine style — unassisted from ski lifts and with all the gear needed to ascend and descend the mountain — is a goal that I set for myself in August 2018 when I arrived in Chamonix. It’s easy to be inspired in a new place. I consider alpine style the purest way to crest a summit and, with the lifts closed, it was also the only way up.

This isn’t an impossible climb, but without access to lifts, it’s something that many wouldn’t imagine doing. I saw it as an act of creativity and challenging the guidebook status quo.

Aiguille du Midi rests at the end of a series of jagged peaks called the Aiguilles de Chamonix (needles of Chamonix). It’s also the tallest ‘needle’ at 3,842 meters (12,604 feet). Mont Blanc stands almost one thousand meters higher, but Aiguille du Midi is the center of attention when viewed from the village. It rests prominently in the foreground, making Mont Blanc, the tallest mountain in the Alps, seem nondescript.

2:30 AM: April 2, 2021. Soft lights lit a small coffee maker, bowl of porridge, and banana. My skis, boots already clipped into the bindings, were secured to my backpack.

3:15 AM: I pulled my buff down to let cool air brush my cheeks as I walked through the empty streets of Chamonix. I was already 15 minutes behind schedule, but I knew I would need those last few sips of coffee today.

I was optimistic and apprehensive about the magnitude of the climb and subsequent Valle Blanche ski descent. Could put my eagerness to achieve my goal aside and turn around if conditions weren’t optimal?

My tension eased as I started using my ski poles on the trail leading to Plan de l’Aiguille — a trail that I’ve followed a hundred times for hikes and runs, but never in the middle of the night. Occasionally, my skis knocked tree branches and pushed me off balance.

At 400 meters, I swapped my runners for ski boots and began ascending on skis. Glowing lights were visible through the trees. I wondered if anyone saw my headlamp zig zag through the forest.

Bullet hard frozen snow made everything slow. My strides were small. I planted my ski poles firmly for every kick turn. Going fast would increase the possibility of losing friction between the ski and the snow.

6:30AM: “Patrick, is that you?” I yelled, approaching the Buvette du Plan de l’Aiguille. Patrick had skied up the night before to sleep outside. I wanted to stick to my vision and do it in a single push from the valley.

“A fox ate my fucking breakfast,” he replied.

As we sipped tea and prepared our gear, Aiguille du Midi, first flanked by the moon over her shoulder, then lit from the sun’s radiation, showed her majestic north face.

Patrick led the final stage of the approach across the Glacier des Pèlerins and over the moraine that follows the Grand Mulet route to the summit of Mont Blanc. I lagged behind Patrick’s swift pace.

8:30 AM (~2,600 meters elevation): It was time to climb. We attached crampons to our ski boots, fastened skis to our packs, and began the Mallory-Porter route.

It was like climbing a ladder. Thanks to the firm snow in the couloir, it was as if we did have a lift up to the beginning of the first crux, a small ~20 meter rock step.

At this moment I felt the exposure from climbing without a rope. Every crampon and axe placement was precise. I assumed that every rock I grabbed was loose, and created a body tripod before yanking aggressively, to test its resilience, before I climbed higher.

Approaching the last climbing move, I decided the rope was better off around my waist than in my pack. I went down a meter to a slightly awkward stance. Cracks weren’t where I wanted them to be, but I built a solid anchor using a couple of spring-loaded camming devices and an ice axe. Securing myself to the anchor, I pulled the rope from inside my pack and dropped it to Patrick who connected us to a climbing anchor in a snowfield just above the rock step.

The psychological security of the rope made the climbing easier. My ego remained in check. This stance was our last chance at retreat. Past here, abseils would be difficult and down climbing cumbersome. We agreed to keep climbing.

Winter climbing is generally easier, safer, and more fun when snow is well-bonded to the rocks underneath. The snow we encountered after the crux rock step was sugary, unconsolidated, granular snow, settled, but not connected to the rock, in contrast to the initial snow coulouir.

We moved diagonally left up the snowfield. Our crampon front-points caught buried boulders beneath the snow and the fingernails on a chalkboard joly sent our feet down to a positive edge on the next rock. I shrieked, grunted, and clipped into a few pieces of cord left by climbers from previous ascents. Eventually, the giant serac at the end of Glacier du Géant was looming over us.

Above us, the sun kissed the north-west facing demi-lune (half-moon), where Mallory-Porter connects to Eugster Direct. We drifted right towards this feature in a narrow coulouir, brushing off every rock in a steep gully like a lottery ticket— scratching for jugs for my hands and ledges for my crampon front points.

Noon: A few hundred meters of climbing remained from the top of the demi-lune. Snow conditions improved, but our pace slowed as we approached the last challenge of the day.

On the right flank of the Glacier du Géant, I placed an ice screw and buried Patrick’s ice axes to reinforce an anchor. Dropping the rope coils from my chest, I punched them in a small divot in the snow so they wouldn’t hang down the glacier’s face. Patrick put me on belay.

Moving diagonally was the path of least resistance, with the most potential to place the four remaining ice screws: Left axe left, and up, left foot left, and up, right axe left and up, right foot left and up.

My burning calves asked for more attention than my numb right toes. The 50-55 degree aspect to the glacier was firm as I moved sideways. My body mass rested squarely on my crampon front points and the small fraction of the boot which penetrated the surface. Calves fully engaged, the pressure between my toes and ski boots further restricted circulation in my toes.

My previous winter climbing season ended with a moderate case of frostbite, but now wasn’t the time to dwell on it.

I felt a tug on my harness; I was at 50 meters of rope. Patrick removed the first screw at his belay and we began simul-climbing, a method for moving quickly across relatively easy terrain together. The terrain was high consequence, but low-risk, meaning we were very confident about the climbing, but mistakes would be highly consequential. Screws were our false security. Solid crampon and ice axe placements were the real insurance.

I maintained at least one screw between us until the glacier ice disappeared. The surface morphed into refrozen snow, a useless medium for ice screws. Patrick pulled the last screw, leaving only a rope between us.

Climbing is loaded with decision-making dilemmas. Conventional wisdom says, if you can’t get good gear, you should unrope. A misstep individually punishes us collectively. Even with axes and crampons buried in snow, arresting your partner’s fall would be a monumental challenge. But untying from the rope didn’t make sense. We were confident in the climbing and it was more dangerous to take time untying or digging to place my last ice screw. Moving up was the best solution.

The upper left flank of Glacier du Géant rewarded our patience with solid blue ice. I placed the last screw. More physiological protection.

Finally reaching the end of the ice, I hammered my axes into a wind-loaded snowy lip, searching for a positive hook underneath the surface. Nothing. Down climbing back to the last ice screw, I removed the slack from my rope and belayed Patrick on a munter hitch adjustable knot. When he reached me, I built an anchor with our screws that was strong enough to hold a truck. Feeling the extra security from the belay, I attacked that last few meters of ice and flopped onto the snowy lip above like a killer whale at Sea World.

3PM: Scrambling up the last 20-30 meters, I burrowed down on the other side of a snowy arete — where alpinists trek — leading to the Aiguille du Midi cable car station. Using the friction of the snow against the rope and my weight as a counterbalance, I belayed Patrick to the top of the ridge and we exchanged a collective sigh of relief and some f-bombs.

Mini-bursts of solar couldn’t warm my pallid toes anymore than my rubbing them. Patrick offered his armpit, the best way to re-warm icy hands and toes.

La Vallée Blanche is perhaps the most famous ski descent in the world, and we nearly had it to ourselves—just a couple of skiers heading up. As we passed icy glacial gargoyles on the classic 15km track, I felt how rare the moment was. It was as if we were far removed, in both time and space, from the steep ski and alpine climbing capital of the world.

At the end of the Mer de Glace glacier, where the tourist stairs begin, we marched up towards Refuge du Montenvers. Patrick kept getting smaller in the distance — he seemed to be storing energy like a squirrel. I didn’t try to match his pace.

We finally finished our vertical ascent for the day at Montenvers, a 140 year-plus alpine hotel. I squinted at the sun as it was drifting lower through the haze and a squadron of clouds. Skis back on, we slid through the forest, dodging trees and evading rocks, eventually connecting to the James Bond ski track—so named for its appearance in The World Is Not Enough with Pierce Brosnan. The snow disappeared 400 meters above town. We slipped on our runners, strapped our skis to our packs one last time, and walked toward Chamonix.

April 2, 8 PM: A friend who met us with Fantas and snacks also offered us a ride home from the bottom of the Planards Ski Area. There was a 6 PM curfew because of the pandemic lockdowns, but it was only a 10-minute walk home. Patrick took a ride to get his car, but I was determined to reach the finish line unsupported. I kept walking.